Back in the summer of 2009, I came across a fascinating book called The Atlas of Languages, edited by Bernard Comrie and Maria Polinsky. I spent several days enraptured by its wealth of knowledge, colourfully presented in photographs, charts, maps, fact snippets, word lists and anecdotes, short stories and traditional poems. The book stands out from other ‘language atlases’ not only in its exciting presentation, but also because it never loses sight of the peoples that speak each language and write in each script. Its main message was clear: richness of language and culture is richness of humanity; the beauty and wisdom of a single language, script, proverb, folk tale etc. enrich not only the speakers of that particular tongue, but mankind as a whole.

I revisit the book from time to time to remind myself of how incommensurably wide and diverse the world is. Have you ever heard of Kapampangan, a language spoken by around 2 million people in a small area of Luzon island, the Philippines? Did you know that a variety of French is still spoken today in the coastal areas of Louisiana? That the classical Mongolian script is written vertically? Or that the reason behind the rounded characters of the Dravidian alphabets of southern India (often compared to fruits, as opposed to the ‘hanging laundry’ of the Devanāgarī scripts of the north) was the need for greater visibility amid the sturdy, straight veins of the plantain leaf they were often written on?

Besides the pleasure of learning and of expanding my planetary awareness, the chief delight in leafing through the Atlas of Languages was an enduring feeling of hospitality; I felt as if I was reading an extended version of Walt Whitman’s Salut au monde (a poem he very probably wrote with a trusty globe or atlas next to him on the desk), yet with an important difference: the book was a poem of multiple voices, rather than that of a single poet and his pen.

A crazy idea soon popped up: I wanted to attempt to write a poem that would transmit a similar feeling of planetary hospitality, both graphically (on the page) and rhythmically (in performance). My multilingual sonnets or ‘mosaics‘ had shifted healthily away from personal expression, but had become too programmatic; moreover, as in the book, I wanted the peoples speaking each tongue to be vitally present, with their hopes, dreams, and down-to-earth everyday realities, be they tragic or joyful, or something in between. The idea was to picture an imaginary traveller being welcomed into family homes in different villages across the world; the poem needed to braid a monolingual (Maltese) narrative thread with a multilingual string of words and phrases ‘welcoming’ the traveller-reader.

I spent a good month mining phrasebooks, dictionaries, online language learning videos and the like, selecting simple words and phrases in dozens of well- and lesser-known tongues, listening carefully to their pronunciation (often very difficult to imitate, particularly in the case of tonal languages, such as Tibetan and Vietnamese!), keeping an eye out for their grammatical and cultural particularities, and for their specific music and ‘friendly’ sound. I could have continued this exhilarating research forever, but again, I didn’t want to lose track of the peoples behind and within the words. After that, I can’t remember how long it took me to weave the chosen words and phrases around the narrative Maltese verses (a day? two days?). I could have chosen a less wishy-washy title than Merħba, a poem of hospitality, but it was the obvious statement of intent needed at the time. I wrote the poem in four parts: the welcoming; the drink and the small talk (ever so important in order to relate to people at an elemental human level, as veteran comedian and traveller Michael Palin states in this Guardian article); the meal and the confiding of families’ more personal stories; and the warm goodbyes and good wishes.

I spent a good month mining phrasebooks, dictionaries, online language learning videos and the like, selecting simple words and phrases in dozens of well- and lesser-known tongues, listening carefully to their pronunciation (often very difficult to imitate, particularly in the case of tonal languages, such as Tibetan and Vietnamese!), keeping an eye out for their grammatical and cultural particularities, and for their specific music and ‘friendly’ sound. I could have continued this exhilarating research forever, but again, I didn’t want to lose track of the peoples behind and within the words. After that, I can’t remember how long it took me to weave the chosen words and phrases around the narrative Maltese verses (a day? two days?). I could have chosen a less wishy-washy title than Merħba, a poem of hospitality, but it was the obvious statement of intent needed at the time. I wrote the poem in four parts: the welcoming; the drink and the small talk (ever so important in order to relate to people at an elemental human level, as veteran comedian and traveller Michael Palin states in this Guardian article); the meal and the confiding of families’ more personal stories; and the warm goodbyes and good wishes.

I cannot say how successful Merħba has or has not been in transmitting the feeling of earthly hospitality I was looking for. I no longer recite the poem in public, for different reasons. Some nice things have happened to it: it was launched at the Istituto Italiano di Cultura in Brussels, with actresses Miriam Galea and Loranne Vella (there was a fantastic rhythm and energy at the end of our short rehearsal, but once on stage, I lost my bearings); I recited the English adaptation of the poem at the Berlin poetry festival (there’s a decent recording, and a long image of the poem and its graphical ‘dance’, on lyrikline); the Spanish version (by my good friend Carmen Herrera) was adapted into a ‘spoken music’ piece by artistic collective Proyecto 23, and performed at a festival in Valencia; best of all, the poem took me to India for voluntary teaching work, with thanks to United Planet.

Since my return from India, however, I’ve never read the poem in public again. Perhaps because I feel it doesn’t match the feeling of hospitality I experienced in village homes whilst travelling in West Bengal and Tamil Nadu. The poem lacks simple gestures, aromas of chai and spices, and a very important, at once earthly and mystical feeling: that of the cool floor under the soles of the feet, when removing your sandals to enter a family home; the same floor that the hosts walk on, work on, sleep on, live on. Also, in the central parts of Merħba, there are bits that no longer convince me, where I feel that the rhythm stumbles and falters. Still, the main reason I haven’t given much thought to the poem for the past three years is that I’ve shifted away from the multilingual, and now write almost exclusively in Maltese; not by deliberate decision, it’s just that the Maltese language was there all along, tapping at the door, before softly bashing it down.

Of course, a literary work does not die simply because it’s abandoned by its author; to the contrary, once completed, a poem takes on a life of its own, and it’s best if the author makes no claims to control it nor to guide it on its way. Three years’ distance from Merħba have done me good; too much consciousness of your past writings, good or bad, risks inviting a stilted development of what you may be writing in the present.

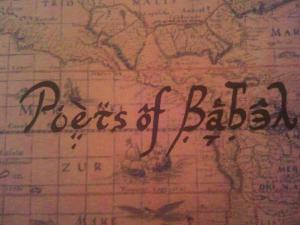

There is one person, however, who is keeping the Merħba poem alive. One year ago today, Shoshana Sarah, a lively poet from Baltimore working for an NGO in Jerusalem, hosted the first monthly get-together of the Poets of Babel writing group in the living room of her house. At the beginning of each event, Shoshana welcomes her friends with lines from the English adaptation of Merħba, whilst others read out some of the phrases in Arabic, Russian, and any other tongues they recognise and are able to pronounce. I’ve been following from a distance, and with a certain ambivalence, due to my scepticism with regard to the poem and the difficulties of its performance.* I’m not sure the poem works if it’s not recited in its entirety; in fact, I’m now realising that the ‘multiple voices’ I was looking for back in 2009 may be less diverse and less present in the poem as I had originally wished. Perhaps one day I’ll re-write it; that is to say, a completely different poem, in a similar but more ‘tangibly human’ vein.

There is one person, however, who is keeping the Merħba poem alive. One year ago today, Shoshana Sarah, a lively poet from Baltimore working for an NGO in Jerusalem, hosted the first monthly get-together of the Poets of Babel writing group in the living room of her house. At the beginning of each event, Shoshana welcomes her friends with lines from the English adaptation of Merħba, whilst others read out some of the phrases in Arabic, Russian, and any other tongues they recognise and are able to pronounce. I’ve been following from a distance, and with a certain ambivalence, due to my scepticism with regard to the poem and the difficulties of its performance.* I’m not sure the poem works if it’s not recited in its entirety; in fact, I’m now realising that the ‘multiple voices’ I was looking for back in 2009 may be less diverse and less present in the poem as I had originally wished. Perhaps one day I’ll re-write it; that is to say, a completely different poem, in a similar but more ‘tangibly human’ vein.

Tonight, for their first anniversary, the Poets of Babel group will not be gathering in Shoshana’s living room, but at the Jerusalem Cinemathèque as a public event. They’ll also be hosting a spoken word open mike, jazz music, and a screening of the film Howl. I wish them the very best of luck! No doubt the event will be an important stepping stone towards one of Shoshana’s dreams: the setting up of an NGO “to create Citizens of the World out of today’s youth via linguistic, cultural, and artistic Creative Education“. Way to go, Sho!

Thank you so much, Antoine! You are an inspiration and I am so moved that you thought of us. Though you have moved on from Merħba, I hope to have the honor of hearing it from you one day. Your words gave me strength, love and joy while on my way to the event and eased my anxieties. I dare say, you and Merħba are the reason Poets of Babel exists. For that I am immensely grateful. Thank you.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on As Open As the Sky… and commented:

I am so moved by this post written by my favorite poet Antoine Cassar who inspired the creation of Poets of Babel!

LikeLike